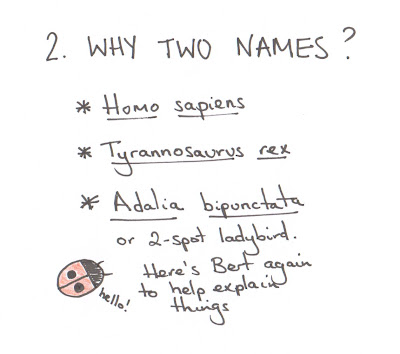

Taxonomy as subject, or rather

how and

why we name things the way that we do, is one of those tricky things that we get asked about all the time.

It's a tricky thing because really there is so much that we could talk about we often don't know where to start. Of course, asking us is a bit like asking a 5 year old polar bear enthusiast to tell you why they like polar bears- soon you will know everything there is to know about polar bears and probably a bit more on top. It's the same with us and insect related questions, we just can't help but get over-excited and try to tell you absolutely everything there is to know. Considering that there are over million described insect species and hundreds of years of history to taxonomy, collections, museums and science it's not surprising that staff can still be talking days after you ask your original question.

So here, in jaunty cartoon format are the pithy answers to the two most commonly asked taxonomy related questions:

Latin is a universal language. It doesn't matter which country you are

from or what language(s) you speak, using a latin name for a species

allows you to be precise about the species you are talking about, so if a researcher in Spain communicates about a species with a researcher in Malaysia they know that they are both talking about exactly the same thing.

Sometimes, species end up with multiple common names. There is no code or list of rules for giving a species a common name (which there is when it comes to latin names) and so some species end up with lots of different names. Ladybirds are variously known as: lady bugs, lady beetles, god's cow, ladyclock, lady cow and lady fly among others.

Various taxonomical systems have been employed in the past. The

binomial system (2 names) as refined and perfect by

Carl Linneaus is the one that is now used by taxonomists. A trinomial name system (3 names for a species) was in existence for a while but it was found to be too cumbersome, as were a few other systems that we will touch on in future posts.

The other advantage to using a binomial system is that it lets you reuse specific names for multiple species across different genera. The rules do not allow for generic names to be used more than once so you can never completely duplicate a name. For example all the following species have a specific name of punctata but belong to different genera, hence you can differentiate between them:

Platythyrea punctata (an ant),

Phyllorhiza punctata (a jellyfish),

Drepane punctata (a sicklefish) and

Tangara punctata (a bird).

Taxonomical systems are all based on the above format. Levels within a system vary depending on the subject, for example, a zoological structure dealing with mammals has a higher level structure, plant structures are complicated by hybridisation and insect based trees have an extraordinarily high number of branches due to the sheer volume of species involved.

Further levels are available to a taxonomist than those above. There are both super- and sub- levels for each category (super-family or sub-order for example) as well as extra levels such as tribe which is inserted between family and genus. In fact, there are multiple variations around a theme and all of these structures are flexible. A classification scheme is merely something that is imposed on nature by humans as a way of grouping similar species together. Each levels creates a group of a greater or lesser size. Those at the top of tree (kingdom, phylum) create the biggest groups with each group becoming smaller as you move down the list until you reach species level which classifies to a single unit: one species.

The information in this post has been boiled down to the basics. We will cover things individually and in more depth in later posts, when we can take a look at separate issues and discover more about how taxonomists set about sorting out and identifying species, describing new insects and establishing type specimens.

For now though, we hope that you have enjoyed meeting Bert the ladybird. If you have any more questions for us then please post them in the comments box below or e-mail us using entomology@oum.ox.ac.uk.